They’re the missing link, the evolutionary lost boys. Not a fossil or a dried-up dinosaur turd but a living, panting, gibbering pack of big city anthropoids, the New York Dolls carried the fool’s gold genes of glam rock and passed them on to the monkey horde of punks who followed close behind.

Glam rock, at first and second glance, was about nothing more than absurd clothes, gobs of makeup and alien aliases. Suburban kids dressed up as outer space drag queens, with feather boas, platform shoes and skintight silver pants. Scrawny white guys with boring names turned themselves into Ziggy Stardust, Eno, Gary Glitter, Jobriath, Johnny Thunders and Sylvain Sylvain. Glam is show-biz, and often is shrugged off as a fleeting shock wave from the gay-lib explosion, androgynous and pan-sexual youth gone wild on stage. And there’s no question that straight boys dressed as transsexual hookers are pushing (or at least slouching against) the walls of sexual order. There’s also the druggy halo to consider: heroin, cocaine, and speed were part of the seedy street-chic.

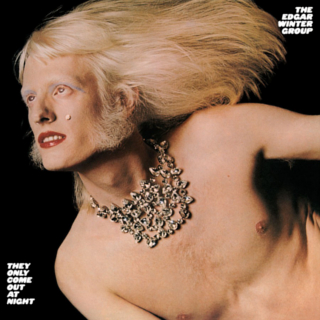

Still, there’s an unspoken, largely unseen element that looms here: something faintly gleaming in the corners of the mind like albino radiation sickness or nacreous moonglow. Glamor, we never forget, is in the oldest sense of the word about bewitchment. “Glamor” meant a magic spell or charm.

David Bowie sang about the “homo superior” in 1971 and about “making the wild mutation” a year later. Deodato put Nietzsche’s Uebermensch into heavy radio rotation. This isn’t progress we’re talking about, but transformation. This isn’t high tech shiny-future optimism, but real teratism - monster making. Mutants usually are highly unadaptive, often flat-out harmful to species survival. The New York Dolls got lost in the gene-jungle, pop culture natural selection making sure there were no direct offspring, no Darwinian success. They were five skinny white boys who mutated into nightmare Ken dolls - five versions of Barbie’s sexless mate dressed up as man-sluts and singing about their “Personality Crisis.” These Kabuki Kens, however, have real bulges in their pants. They’re anatomically correct and when the drugs allow, they’re ready to rut and shoot some bad seed.

Still, they’re both menacing and absurd, with their teased-up hair, gleaming lipstick, scarves, blotches of rouge and pubescent pouts. They never lost their confusion. Were they bad boys or sleazy fashion victims, sexual predators or kids playing dress-up? Later, they’d plumb the depths with too much junkie business, crashed careers, early death and the bass player converting to Mormonism. Always, though, they maintained their unapologetic stance: rude, crude, loud and wild.

There’s a “Lonely Planet Boy” and a “Jet Boy” on this album. Mostly, though, they stay in the street, bumping and grinding through “Bad Girl,” “Pills,” and “Trash.” Two largely overlooked songs point to something far more disturbing that drug-punk bad-assitude. Both are about tainted birth, the genesis of the Baleful Other. They’re not just sex songs, but confused, obsessive leaps into the pit of bio-reproduction.

After “me,” the word “baby” is probably the most common in rock and roll lyrics. In “Vietnamese Baby,” however, the Dolls are talking about about real conception and newborn spawn, the bastard offspring of a U.S. soldier and a nameless, faceless girl on the far side of the globe. The song starts and ends with a cliché Asian gong. In between there’s the standard proto-punk riffs and railing. As music, it’s okay. As a shout of confused dread (“talking ‘bout your overkill!”) it’s definitely not okay. We never know who’s the “you” of the song or why she’s got a Vietnamese baby on her “pretty little mind.” But we do understand that something is very wrong and it’s not going away.

The third Frankenstein song of ‘73 (labeled “original” on the album cover) was the last one of the year. Again we’re in movie-monster land - “shoes too big, jacket too tight.” And again Frankenstein stands for something ill-defined and intolerable. The song starts with an image of war, or biological disaster. “Something must’ve happened over Manhattan.” It quickly gets more personal, a repetitive, far-too-long track built mostly on unanswered questions. “Who could’ve spawned all the children this time?” We never find out. “Do you think you could make it with Frankenstein?” Is this about sex with a monster or is “make” here about literally making a baby, the nameless “it”?

1973 was the year of the American abortion. In January, Roe v. Wade transformed the country’s relationship with its unwanted offspring. Frankenstein’s creature calls himself an “abortion” and here on the Dolls’ first album he returns again: the divine portent of misfortune, the monster-spawn who may be loved, but who must be destroyed.